Lammas and Lughnasadh: Celebrating the First Harvest on August 1st

- Aug 1, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Aug 4, 2025

In the hedgerows of August, when the blackberries begin to blush, the apples start to ripen and the barley fields sway heavy-headed in the breeze, high summer has reached its tipping point. The sun still warms the body and land, but the shadows grow longer, the light more amber. This is Lammas—the festival of the first fruits, the first loaf, the start of the harvest. Lammas, or Lughnasadh, is a festival marking the first harvest, celebrated on August 1st in the British Isles and beyond.

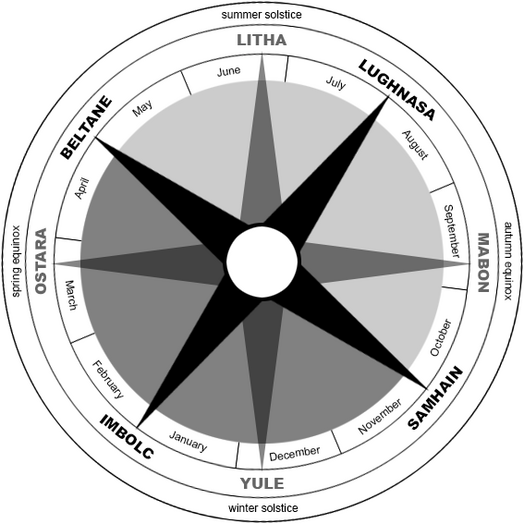

Lammas—once Loaf Mass—though the festival’s older name, Lughnasadh, survives in Irish tradition. In the British Isles, this cross-quarter day stands between midsummer (Litha) and the autumn equinox (Mabon) on the eightfold wheel of the year. It marks a subtle but profound shift: from growth to gathering, from light to letting go.

Its roots run deep into our ancient soil. Long before Christian feast days, this was a time of offering and thanksgiving. Across Britain, Neolithic communities built ceremonial landscapes aligned to the rhythms of sun and season—stone rows, enclosures, and cairns that watched the sky and listened to the land. The turning of the agricultural year was more than practical: it was sacred.

“It was upon a Lammas Night

When corn rigs are bonny,

Beneath the Moon’s unclouded light,

I held awhile to Annie…”

Robert Burns

In Wales, the day was known as Calan Awst, and while little survives of its earliest forms, hilltop gatherings, fairs, and the racing of horses on uplands suggest a continuity of seasonal rites that echo the Lughnasadh assemblies across the Irish Sea.

In Ireland, Lughnasadh—named after the god Lugh—was a festival of first fruits and communal renewal. Lugh, the many-skilled champion, is said to have established the games at Tailtiu in honour of his foster-mother, who died clearing the land for agriculture. Though the myths differ, the underlying spirit—gratitude for labour, reverence for land, the cycle of life and death—resonates across all these traditions.

Lammas, then, is not a triumphant harvest home, but a threshold. The grain is cut at its peak, its life surrendered to feed the people. Like the figure of John Barleycorn, whose tale was passed in English folk song and seasonal drama, the spirit of the crop is sacrificed—cut down, ground, baked, and eaten—only to rise again in the spring.

In parts of northern England and Scotland, echoes of this time survived into recent memory as Lammas Fairs, held on hilltops, commons, or church greens. These were not just markets, but ritualised gatherings: games, music, wrestling, matchmaking. In some regions, people climbed sacred hills—Ben Lawers, Slieve Donard, Carn Brea—as if reaching towards the sky could rekindle the fading fire of the sun.

Today, we live further from the rhythms of the land. Our wheat is harvested by machines, our bread comes bagged and sliced. But Lammas still murmurs in the fields: in the hum of bees, the scent of ripe grain, the hush of a hot evening when the air itself seems to rest.

So bake a loaf. Walk an old path. Visit a hill. Offer thanks—to the land, to those who worked it, and to whatever remains of the old agreements between people and place.

The Wheel Turns.

Climbing the Hill at Calan Awst: First Fruits and Forgotten Fairs

Lammas is only one name. Across Britain, the same moment in the calendar was once known by many titles—the aforementioned Calan Awst in Wales and Lughnasadh in Ireland, as well as Laa Luanys in Scotland and the Isle of Man. Each speaks to a long continuity of seasonal observance: the time when the first harvest is tasted, shared, and given back in thanks.

Though our memories are often local, the roots of these rites stretch far beyond these islands—into Brittany, Iberia, and even the Mediterranean world. Across this great sweep of Western Europe, the start of harvest was once marked with a familiar choreography: hill gatherings, communal meals, games, and offerings of the year’s first grain, grape, or fruit.

Calan Awst and the Welsh Upland Tradition

Calan Awst, or “first of August,” marked the harvest with upland fairs where horse races and courtship dances wove commerce with ritual, echoing ancient communal bonds. In Ireland, Lughnasadh honoured the god Lugh, who founded the Tailteann Games at Teltown in County Meath to commemorate his foster-mother Tailtiu, who died clearing land for agriculture. These gatherings blended feasting, music, and trial marriages, with pilgrims climbing hills like Croagh Patrick to mark the first fruits. Across both regions, Lammas was a threshold of gratitude, where the cycle of labour and land was celebrated in community.

Lughnasadh and the Games of Lugh

In Ireland, Lughnasadh is far better preserved. The god Lugh, whose name gives the festival, was said to have founded it in honour of his foster-mother Tailtiu, who died after clearing the great central plains for agriculture. At Teltown in County Meath, thousands would gather for what became known as the Tailteann Games—a ritual assembly that outlasted its origins by centuries.

At Lughnasadh, people climbed hills, made trial marriages, settled legal disputes, and shared in feasting and music. Similar traditions took place on Croagh Patrick, where Christian pilgrimage layered over older summer rites, and on countless smaller hills across the Gaelic world.

The act of climbing—of reaching a height to mark the first fruits—is a widespread custom. And it is not confined to these isles.

To the South: Brittany and the Grain of Memory

While Lammas is deeply rooted in British and Irish soil, its themes of harvest and gratitude echo across western Europe, from Brittany’s pardon festivals to Iberia’s highland gatherings. In Brittany, ancestral ties to the land are just as deep. Though Catholic feast days eventually absorbed many pagan observances, seasonal fairs, pardons, and processions still follow agrarian rhythms. In late July and early August, certain pardon festivals coincide with grain harvests, often tied to specific saints—yet beneath them one sometimes senses older layers: rituals of blessing the field, offering bread or corn, and walking boundaries.

There are tantalising clues in place-names (linked to Lugh, for instance), midsummer fires, and stone circles repurposed for saints’ processions. In Brittany as in Wales, folk Christianity often walked hand in hand with pre-Christian timekeeping.

Iberia and the Mediterranean: The Fire and the Fruit

Further south, the Iberian Peninsula preserves many traditions that echo the Lammas moment. In Galicia, the Rapa das Bestas and other highland festivals in July and August often involve gathering communities, ritual contests, and communal feasts. The emphasis may fall more on livestock or fire, but the seasonal pulse remains.

In Catalonia and northern Spain, harvest-time brings the blessing of fields and bread, along with candlelit processions, and in Portugal, the Festa das Colheitas—Harvest Festival—is still celebrated in some villages in early August.

In the Mediterranean, too, the first fruits were once central to religious life. The Thesmophoria and Eleusinian Mysteries of Ancient Greece, though focused on autumn, share themes of grain, sacrifice, and renewal that parallel Lammas. Offerings of the first grape or olive oil, often in early August, are known across Southern Europe, tied to local saints, but shadowed by older gods.

Across the Hills, a Shared Memory

In a world of mechanized harvests and supermarket shelves, Lammas invites us to pause, reconnect with the land, and honour the cycles that sustain us—whether through a homemade loaf or a moment of gratitude for the season’s bounty. This reconnection with the cycle of the year joins all these rites—whether on Teltown Hill, a Welsh moor, a Breton pardoner’s path, or a Galician village green—is a shared gesture: the act of offering the first of the harvest, not in private, but in community.

The hill, the loaf, the game, the fire—these are echoes of an old understanding, that the fruits of the land are not ours alone, and must be acknowledged, celebrated, and shared.

And though many of these festivals have faded or transformed, the land remembers. You may still feel it, on a quiet upland track in August, with the air humming and the fields turning gold—the sense that this was once a place where people came together to give thanks, and to begin again.

Dr Alexander Peach.

1st of August 2025

Very interesting, thank you sharing this.

Subscribe for free

Lovely!!